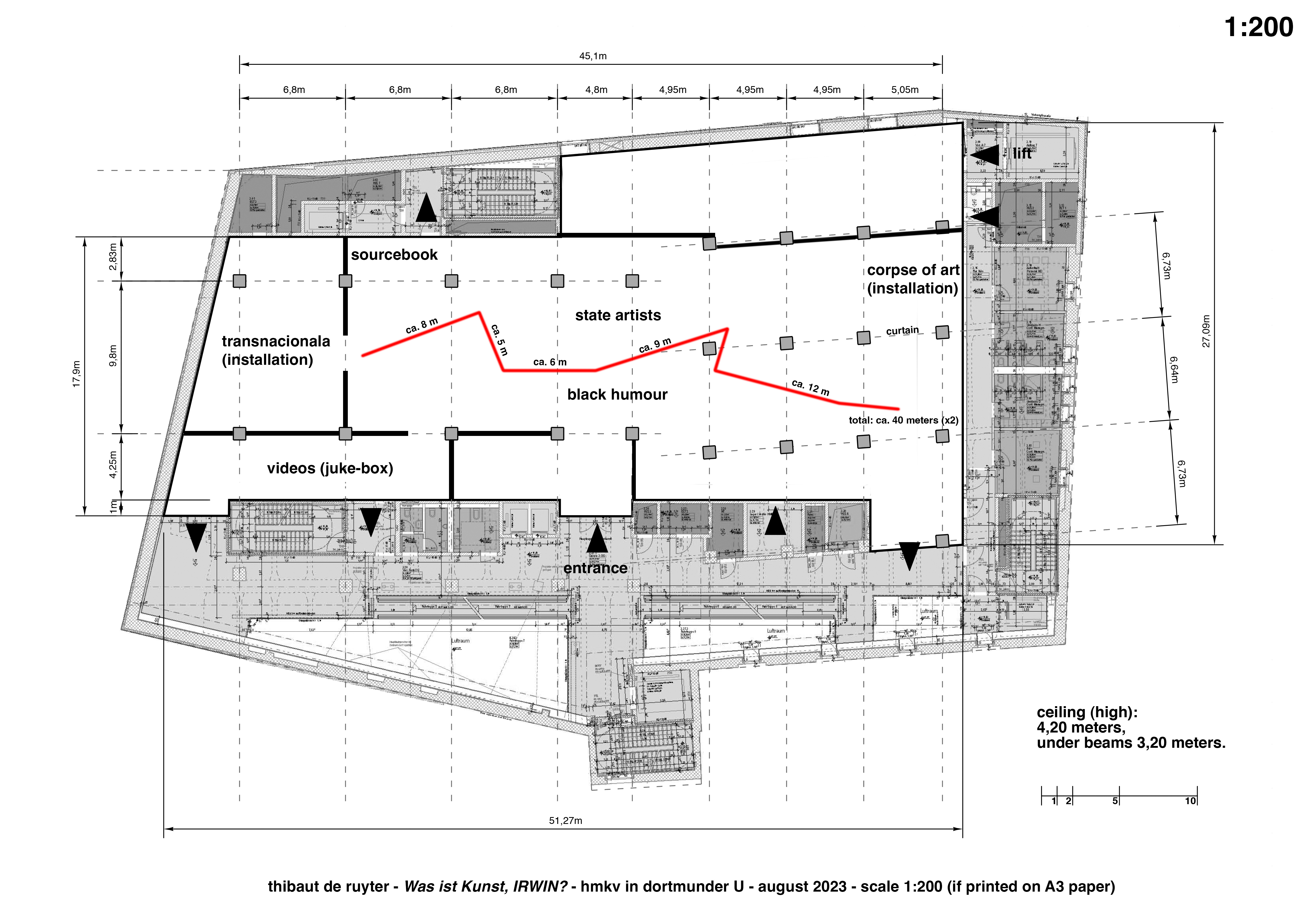

Was ist Kunst, IRWIN?

The exhibition consists of two major chapters. The first exhibition chapter, curated by Thibaut de Ruyter, explores the black humour that is always present in IRWIN’s works. The other chapter, curated by Inke Arns, is dedicated to questions of state – and how IRWIN uses them to comment on contemporary issues such as migration.

Black Humour

The term black humour became widely used after the publication of André Breton’s Anthologie de l’humour noir in 1940. Breton focused on literature, but black humour is now common in films, Internet memes, cartoons, art and family jokes. Like every form of humour, it is difficult to define – what makes me laugh might not work for someone of a different age, social background or culture, etc. – but generally we can say that it is underpinned by a serious, even desperate and pessimist stance. It observes the world as it is and, instead of passively accepting it, makes a joke of war, death, depression, oppression, ideology. It often mocks itself rather than attacking others. It is a provocative kind of humour that pushes the boundaries of bad taste, of permissible thoughts, and political correctness. With roots in literature, Surrealism and the interwar period, it does not shy away from absurdity and violence, from connecting seemingly unconnected events or facts, or from political criticism. The very definition of IRWIN’s art, you might say.

A Matter of Taste and Theory

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu offered a new definition of the Marxist concept of capital by adding the adjectives ‘cultural’, ‘symbolic’ and ‘social’ to the term. But he also made it clear that (bad or good) taste, access to culture and understanding of art are determined by social class and family background. Whether we appreciate something or not is influenced by external factors and education. By manipulating the idea of (good) taste and explicitly quoting Bourdieu , IRWIN question not only their own geographical, historical and social origins but confront the world at large with its contradictions. But Bourdieu is not the only theoretician referenced in their art: IRWIN have famously dedicated pieces to the likes of Slavoj Žižek, Hugo Ball and Lenin. The notion of kitsch which is supposed to distinguish the clever and educated from the ignorant – plays a big role in their work as well, which use popular traditions and tropes (mountains, deer, folk costume...) to provoke the establishmen and the globalised contemporary art world.

TWINS

On 1970s studio photos of young twins, a metal toy aeroplane emblazoned with IRWIN’s trademark black cross partly covers the image. This work is of course a direct reference to the September 11 attacks of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York. All of us have repeatedly watched the images of the two planes hitting the buildings, yet none has ever seen the victims. There exist a few terrifying videos showing falling bodies from afar, but historical documentation focuses on the burning buildings and crumbling towers – abstract depictions commonly found in Hollywood films. In IRWIN’s artwork, the children on the photographs become the casualties of the terrorist attack. The focus thus shifts to the human aspect of the tragedy, reminding us that besides the towers, human destinies have been shattered. The work’s (black) humour is provocative, yet it message is clear: several hundred people who were once smiling children lost their lives on that day.

The Power of the Frame

Frames are an integral part of IRWIN’s aesthetic and artistic production. They function as tool for appropriation but also as an identification or signature. In some works, IRWIN push the concept even further by creatin a ‘frame in a frame’, or mise en abyme. Recently, they applied their iconic black frames on the windows of a house in Ljubljana, supporting the suggestion that IRWIN could frame anything to make it their artwork. This echoes Marcel Duchamp’s observation that if you put something on a plinth in a museum, it becomes an artwork. By doing so, they invite us to reflect on what makes an artwork. The fact that is it framed, signed and exhibited in an institution? What do we identify and recognise first: the frame or the painting? And once the concept of frame has been established, does it even need to ‘contain’ something?

Hommage(s) to the (Black) Square

The Black Square – originally painted by Kasimir Malevich in 1915 – has been a recurrent motive in IRWIN’s production since the collective started working together in the 1980s. It is not only a reference to the long history of avant-gardes but also an icon in the spiritual sense of the term. By painting the Black Square printed on a tote bag of an American museum, IRWIN make fun of its appropriation for global merchandising. They have shown that you can also use Lego bricks to make a black square (suggesting that art can be child’s play sometimes) or use it as a moustache reminiscent of Charlie Chaplin/Adolf Hitler. What has the (black) square to do with (black) humour? The black square is an invitation to look beyond the surface, to reflect on the intellectual, conceptual or spiritual existence of artworks. To understand that even the most abstract of works is charged with thoughts and emotions those of its author but also those of historians, critics and viewers – and therefore becomes a matter of interpretation.

‘It’s not me, it’s him...’

One strategy to unsettle spectators consists of sowing doubts about the authorship of an artwork. During their long career, IRWIN have repeatedly collaborated with, or re-enacted works by, other artists. A photograph showing the collective alongside Marina Abramović was produced as an edition of three, signed respectively by the photographer, IRWIN and Abramović – the price of each work dictated by the renown or market value of its signee. But their play with references and names goes further: a Suprematist composition is painted in Gerhard Richter’s trademark blur while a Mondrian-like composition serves as the backdrop to a coffee cup or is associated with the Christian cross, emphasising the iconic power of early twentieth-century abstraction. IRWIN also pay homage to their predecessors, recreating important performances from the Slovenian OHO group, the original black-and-white documentation now appearing in colour. In all these works, what could be a simple joke becomes a critique of the art market or a way to shed light on lesser-known or forgotten practices.

Corpse of Art

Kazimir Malevich died in Leningrad on 15 May 1935. His body lay in wake for several days in the House of the Artists’ Union before it was cremated and his ashes were buried under a tree in Nemchinovka, near Moscow. Nikolai Suetin, another Suprematist artist, organized Malevich’s funeral and designed his coffin – a cross-shape tin box decorated with a black square and a black circle. The artist’s corpse was surrounded by a selection of his paintings and white lilies. Family and friends came to pay their last respects – not only to the person but also to his art. The mourning became an exhibition in its own right, albeit a slightly uncanny one. In 2003, IRWIN built a perfect copy of Suetin’s coffin and exhibited it with a waxwork dummy as the Corpse of Art, a work that speaks of art history, but also of the absurdity and cruelty of exhibitions. A restaging of a famous exhibition, it is an ‘exhibition of an exhibition’ that retains all the bizarre and eccentric qualities of the original.

State Artists (curated by Inke Arns) & Was ist Kunst, Bernd und Hilla Becher?...