&

The exhibition & is an attempt to dive into artistic practice and aesthetic experience. It is an invitation to enter a world composed of mazes, déjà-vu, subtle similarities, strange symmetries and unexpected discoveries.

Paying an indirect and discreet homage to Gilles Deleuze’s doctoral thesis titled Difference and Repetition, the coordinating conjunction AND, associating two words, becomes the title of the exhibition but is reduced to a typographic sign (called in english ampersand), an abstract symbol resembling a maze or an infinite loop.

Many artists might tell you: an artwork often repeats its predecessor but carries something slightly different. There is an inherent repetition in artistic practice based on the hope that the next work will always be better than the previous one. But everybody can also easily get lost by repeating the same gesture over and over, the same situation, without noticing that it has become a trap. So are our days: we sometimes feel as if we are living in a maze where all paths will inevitably lead us to a similar place, whilst still hoping that something might change.

The hanging, presenting more than 100 drawings of Wacław Szpakowski but also a large selection of minimalist works of Cécile Dupaquier, diagrams by Suzanne Treister, videos from Aneta Grzeszykowska, models by Anna Orlikowska, strange visions by Henryk Morel or silkscreens by François Morellet play with the principle of difference & repetition to create an exhibition in the shape of an aesthetic maze.

Not only minimalism and abstraction are strongly linked historically to the concepts of difference & repetition, also the actual technologies that we use in our everyday activities are regulated by these words. They become the rules of a game that could be a labyrinth, an artwork, the Internet, our lives, but where, at the end, we might not find an exit.

Cécile Dupaquier’s (born 1970) artworks are the latest addition to the history of abstraction. In her recent series entitled Tableaux (2016–17), the artist bends thin sheets of plywood over slightly curved wooden structures that she paints white afterwards. If the result looks at first like a white canvas — a kind of ultimate abstraction where even geometric figures are missing — the whole object becomes the artwork. Her tableaus should be seen as sculptures hanging on a wall, both sharing the same immaculate colour. The construction of the works uses the skills of a violin maker, and, if the viewer wants to really understand the so shapes that Cécile Dupaquier produces, it’s not by looking at the white surface but in focusing on the shadows that they produce on and around themselves.

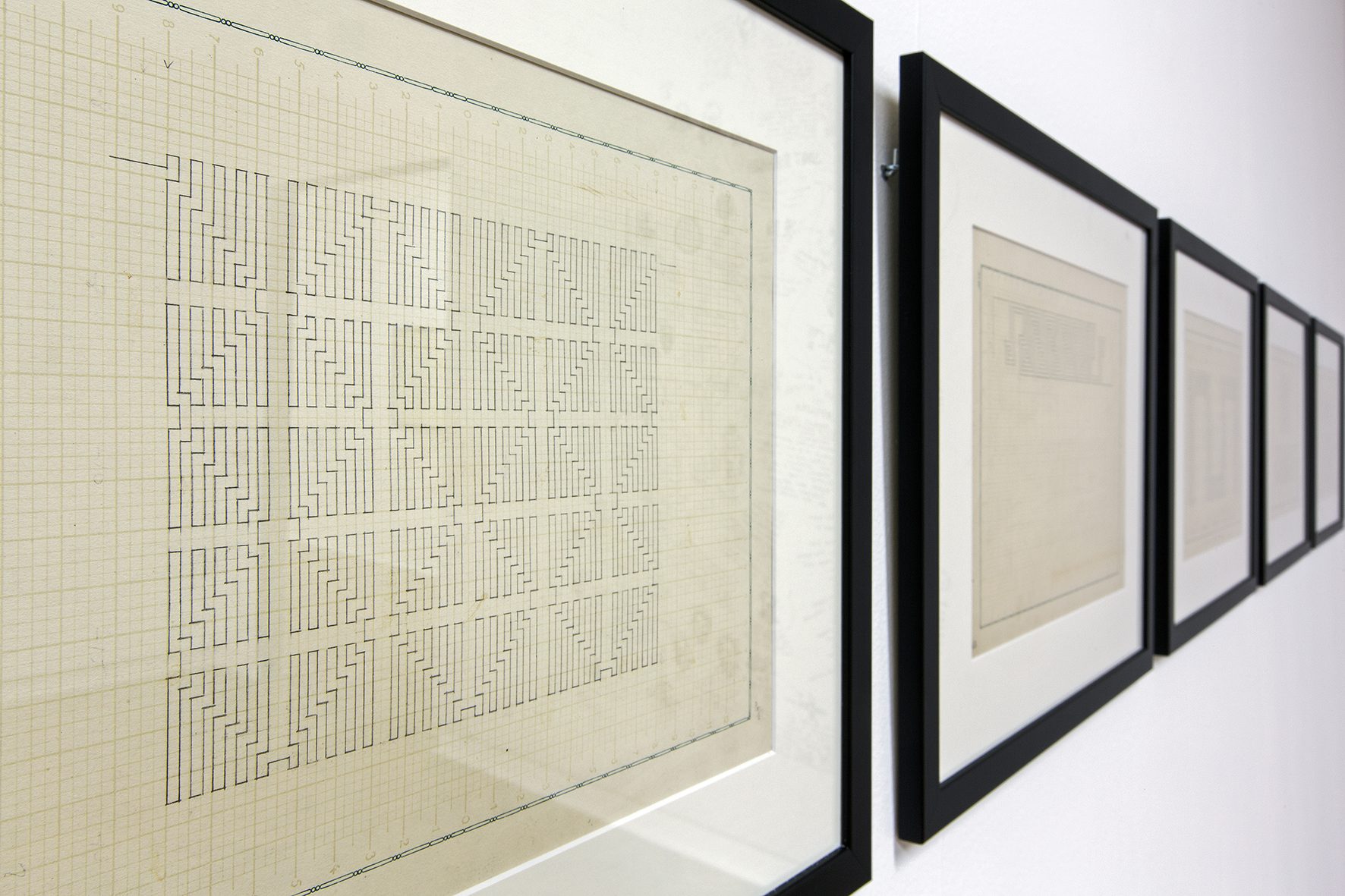

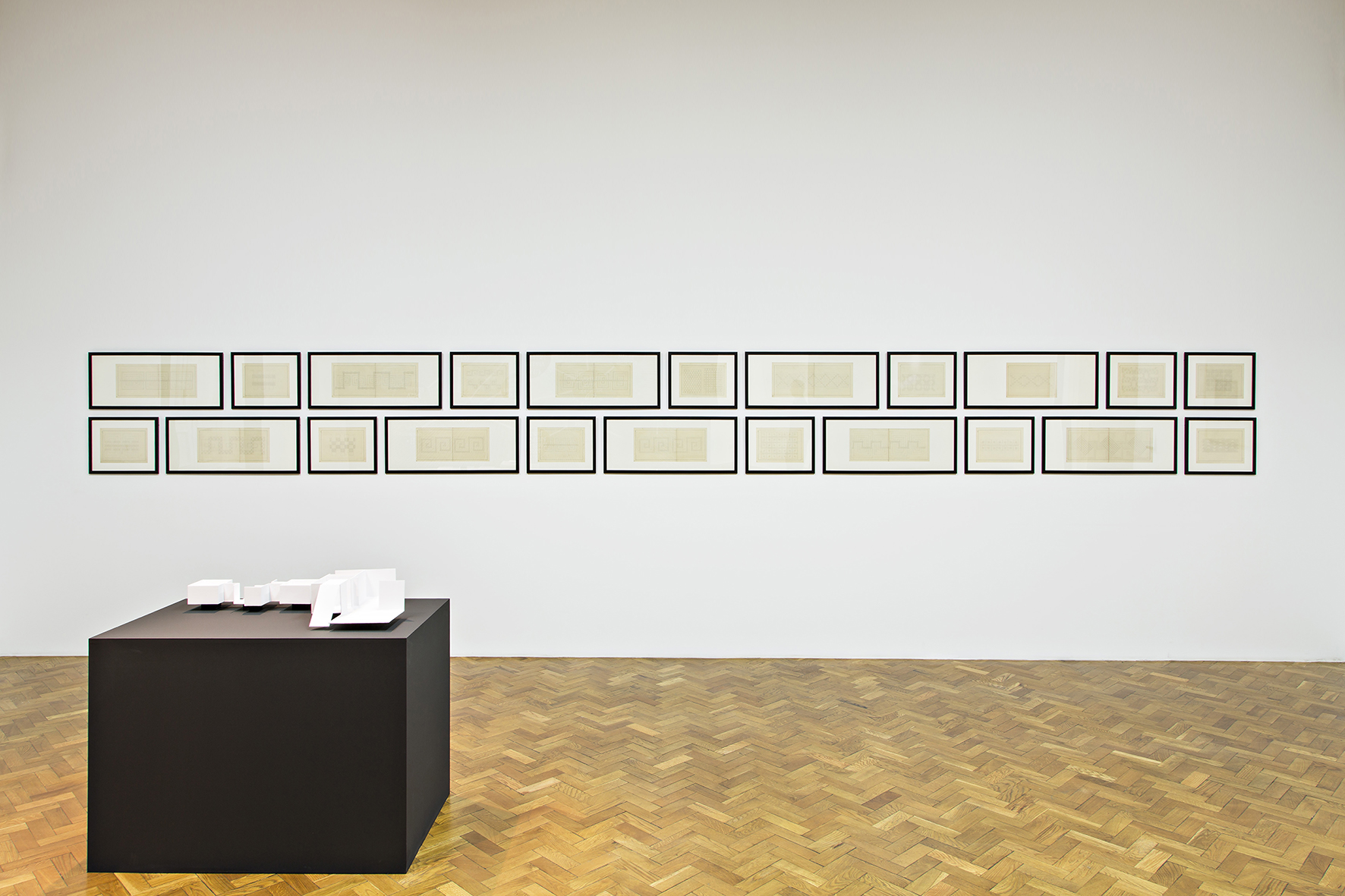

The drawings of Wacław Szpakowski (1883–1973) could easily be interpreted as labyrinths. His black lines on graph cardboard are an invitation to follow a path (like the thread that Ariadne gave to Theseus to find his way out of the labyrinth and escape the Minotaur), but real mazes have a more complicated design, and Szpakowski’s works are more of a surprisingly beautiful and early research on geometrical abstraction. Already in the 1920s, with the very simple difference that he creates within the repetition of his lines, he sometimes creates a visual effect that will, decades later, be used by the artists of the Op art movement (even if they had never heard about him at the time). But the real beauty of his works resides in the fact that Szpakowski, who was an architect, never gave an explanation or a theory for these artworks, which could easily be drawing exercices or the tiny (but in this case very precise) scribbles that we sometimes make while listening to somebody on the telephone.

Mazes and their spatial interpretation as a simple white cardboard model and a more finished production in steel can be found in the sculptures by Anna Orlikowska (born 1979). With Spatial Composition I, II & III (2008) the artist pays an ironic but subtle homage to the aesthetic of Katarzyna Kobro (1898–1951). But the monster in the “mazes” by Orlikowska is a paedophile who created some secret spaces and chambers in his basement to keep his victim separated from the world (the artist used several graphic representations published by newspapers to create her compositions that in no case depict reality). Those works brings us back to the 1920s, to Kazimir Malevich’s architektons and their abstractions of architecture but add a political and social level about mass media and their everyday voyeurism.

The diagrams that Suzanne Treister (born 1958) draws are based on the history of computers, weird science, and conspiracy theories, on facts and presumptions. Making the “invisible visible” by depicting unknown links and surprising connections among inventors, philosophers, novelists, and politicians, they blur the border between science and ction. Many diagrams in the exhibition come from a series entitled Hexen 2.0 [Witches in German] which, of course, draws us back to the original story of the gothic cathedrals (where the first graphic mazes where built in the twelfth century) while others teach us about the unconscious, dreams and hallucinations. If it is easy

to get lost in the complexity of those diagrams they are, at the same time, a way of learning a different path in history.

The three videos titled Black (2007), Bolimorfia (2008 / 2010) and Headache (2008) by Aneta Grzeszykowska (born 1974) all deal with the slow disintegration of the human figure and the infinity of space. By using black clothes on a black background, she makes her body disappear bit by bit, in a sometimes funny, dramatic, or erotic choreography. The videos relate to the history of the Avant-garde and the early age of cinema. One might think of Man Ray (Meret Oppenheim at the Printing Wheel, 1933), Herbert Beyer (self-portrait, 1932), or Oskar Schlemmer, who all played with fragmentation of the body through very simple special effects that didn’t need computers but only mechanical skills and invention. At the same time, while looking at the artist getting lost, submerged in darkness, it is difficult not to think about the men dying in the oneiric science- fiction movie Under the Skin (2013).

The ten drawings by Henryk Morel (1883–1973), composing a series entitled Lunapark, were produced between 1966 and 1968. They are not representative of the artist’s production – who is more famous for his brutally abstract sculptures made at the same time with rusted steel and rubber tires – but they carry an apocalyptic vision and a disturbed inner world that takes us to the middle of a dangerous labyrinth. Be- tween Piranesi, Gustave Doré, and Alfred Kubin, Mo- rel’s Lunapark is not a place for entertainment but

a territory of hallucinations and nightmares. Black birds and young naked women inhabit a world made of dark houses and poisonous vegetation. Somewhere, in these almost Surrealist drawings (Hans Bellmer is not very far), a hidden monster is waiting for us.

Abstraction — between homage to the early Avant- garde and visual effects of the Op art movement

of the 1960s — is to be found in the works of the artist François Morellet (1926–2016). Morellet had

an obsession with simple geometrical lines, their repetition and possible variations following geometric principles but also, sometimes, more random systems (like using numbers from a telephone phone book to define the position of black lines on a canvas). The drawings of Szpakowski, like the paintings of Morellet, play a game of small transformation, adaptation, and variation. But they also teach us that geometric abstraction is not only about perfect proportions and golden section but, also, about chance, humour, and games.

It is probably not a coincidence that one of the first computer games ever produced was a labyrinth. Pro- grammed in 1982 by Malcolm Evans for the famous Sinclair ZX81 home computer, 3D Monster Maze is one of the first successful games that ran on a very simple computer (at that time with only 16 kilobytes of memory!). The graphics in black and white generated a very geometrical perspective and the game is, today, truly dated. But what was at the time a technical challenge can be seen nowadays as a true aesthetic achievement.

For the finissage of the exhibition on November 5 2017, a performance in the frame of the Re:Rosas project by Anne Teeresa de Keersmaeker took place, bringing the original idea of "Difference & Repetition" to the field of dance and music.

&

Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź (Poland)June 30 — November 05, 2017

Curated & architecture by Thibaut de Ruyter

Coordinator: Katarzyna Mróz

Graphic Design: Aleksandra Matyas

Supported by: Oldenburger Computer-Museum

Artists: Cécile Dupaquier, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Katarzyna Kobro, Henryk Morel, François Morellet, Anna Orlikowska, Wacław Szpakowski, Suzanne Treister