Neue-Neue Nationalgalerie (François Morellet)

Almost forty years ago, on January 14th 1977, François Morellet inaugurated his first retrospective in Germany, at Berlin’s Nationalgalerie: Bilder und Lichtobjekte (Images and Light Objects). Today, what remains of the exhibition are a few magical black and white photographs, some newspaper articles (in particular, a piece where the artist finds himself named François Morellat [sic] in the Süddeutsche Zeitung) as well as a beautiful exhibition catalogue with a minimalistic graphic design which, at the time, would have cost 28 Deutsche Mark and can now be purchased second-hand for around 20 euros.

Born in 1926, a fifty-year-old artist was then exhibiting around fifty artworks, and it is clear upon reading the publication, that Morellet had come to maturity. His earliest works date back to the beginning of the 1950s, thus some 25 years of his career were being celebrated at the Nationalgalerie. After Berlin, the exhibition travelled to Baden-Baden and concluded its journey at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, demonstrating to what extent Germany was always “one step ahead” in the French artist’s career.

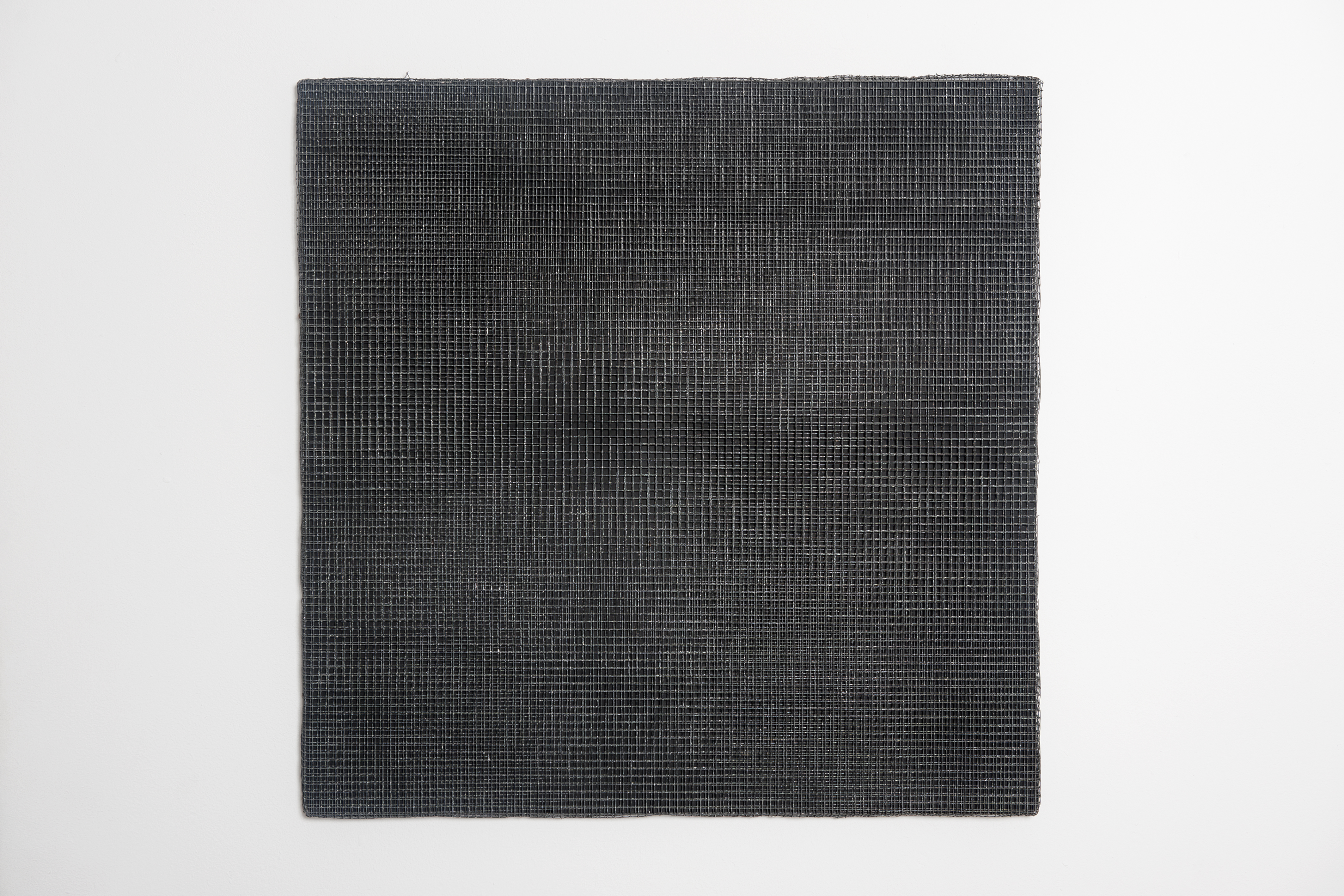

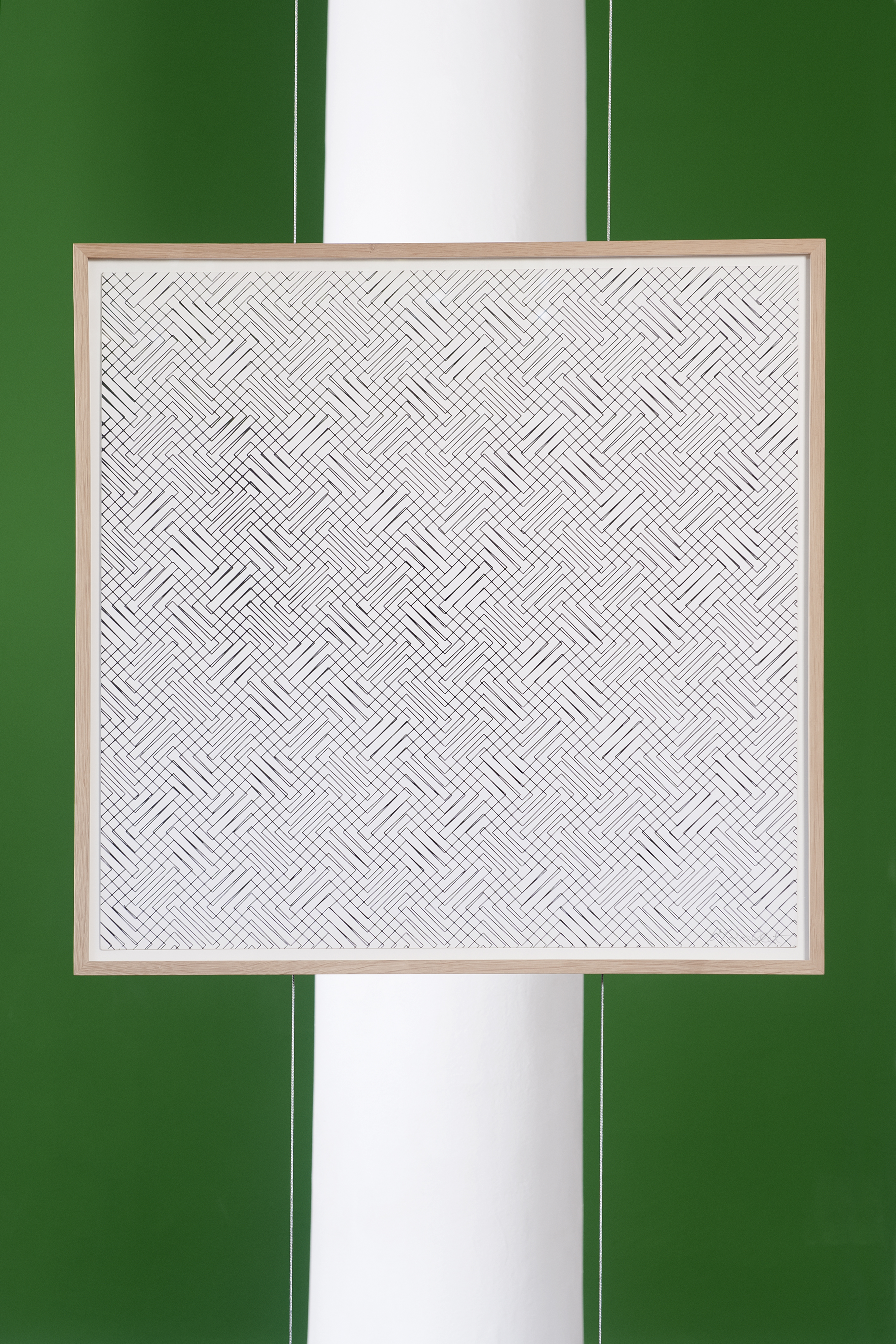

The works presented this autumn at Berlin’s Galerie Jordan/Seydoux were for the most part produced in the decade preceding the exhibition at the Nationalgalerie. These are accompanied by two more recent works (Ondes Parasites, 2014, and Système, hasard et téléphone, 1997) which demonstrate that, for Morellet, the story didn’t end in 1977 and that he always found new ways to reinvent himself through numerous systems. The exhibition Neue-Neue Nationalgalerie showcases a set of six black and white screenprints (Trames produced in 1965), a print entitled Répartition régulière de carrés, 1 sur 2 rouge-rose, 1 sur 2 rouge-orange from 1975, accompanied by three unique pieces: a grille on wood Grillage sur bois (1978), an oil on wood 45° 90° 135°, bleu sur rouge (1971), and an acrylic on wood 0° 60° 120°, noir sur blanc (1972).

The exhibition’s set up in the Jordan/Seydoux Gallery is a tribute to the Nationalgalerie exhibition. When Mies van der Rohe constructed this building in 1968 (the first version of which was in fact the headquarters of Bacardi in Cuba and was designed in 1958), the architect was not really concerned with the artists that would exhibit there. It is with great pleasure that we have seen the elegant Jenny Holzer and the ironic Marc Wallinger pass through this temple of glass and steel. We were able to admire the scenography of the architects Caruso St John for Thomas Demand in 2009, while the last painter to have presented a retrospective there was Gerhard Richter who showed no real interest for the building. The space is so difficult that we have also witnessed many artists fail. Morellet was not only a producer of paintings and works on paper, he also conceived many installations (to the point that the Centre Georges Pompidou consecrated an exhibition to them in 2011 entitled Réinstallations) and his scenography for the Nationalgalerie reflected his interest and ability to play with space. Thus, in 1977, three paintings floated in the main hall, highlighting the absence of walls in Mies van der Rohe’s building, and giving the artworks a special character: they did not require a wall in order to be hung, while their game of lines and angles provided a slight offset and an odd perspective amidst the severe geometry of the German architect. This presentation, singular in the history of the building, is reinterpreted at Jordan/Seydoux, evidently on a smaller scale but with humour which, we hope, would have pleased François Morellet.

A view of the exhibition at the Nationalgalerie (which at the time, was not yet called the Neue Nationalgalerie) and the catalogue from 1977 are the starting point of this presentation. Borrowing the mise en scène of the paintings floating in mid-air, using historical works focussing on the first twenty years of the artist’s career, it is an ambitious project combining prints, unique pieces and a nod to the past. Moreover, it is an opportunity to examine Morellet’s obsession for wefts and grids; it is amusing to think of Carsten Nicolai who published a book entitled Grid Index in 2009. In the style of a scientist, he identifies the hundreds of wefts created by different line assemblies. And this book, in its graphic design, reminds of François Morellet’s catalogue for the Nationalgalerie. This is therefore the lesson that we can learn from this project: from his beginnings, the French artist was a contemporary and his interests continue to exist in geometry, play, humor and space.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Neue Neue-Nationalgalerie

Galerie Jordan/Seydoux, Berlin

September 8 — October 29, 2016

Curated by Thibaut de Ruyter

Artist: François Morellet