Richard Meier - Ein Stilraum

On April 25th 1985, Frankfurt’s Museum Angewandte Kunst (at the time still called Museum für Kunsthandwerk) moved into the Richard Meier building in Schaumainkai 17. On the occasion of its thirtieth year in these quarters, the museum is presenting a cabinet exhibition entitled Richard Meier: A Style Room, which is more than a design show. In it, visitors can learn what historical references the architect drew on for his plans: what early twentieth-century design examples did he look to for orientation, and what cultural contexts of the 1980s underscore his approach?

In a display case in the Style Room, a sober menorah designed by Meier refers to his Jewish origins, which he mentioned with pride in his speech for the inauguration of the museum (recorded in Michael Blackwood’s little-known documentary on its construction). Next to it appear several other objects he designed for the table, including a candle- stick, cups and plates. Their date or materials matter less than the formal and geometrical principles governing them: the square and the circle, black and white, simplicity and mannerism.

Music is one of the best time-travelling devices, as it often determines the atmosphere in a house. More importantly, it can also be a formidable translation of architectural concepts (is not Goethe wrongly credited with saying, ‘I call architecture frozen music’?). »Glassworks«, an album released by Philip Glass in 1982, features music based on minimal (albeit decidedly romantic) motifs, which are repeated with a certain degree of obstinacy. Its function echoes that of the 1.10 metre-long squares Meier identified in the layout of Villa Metzler and on which he based the grid for his modern extension. Simple geometric patterns are repeated, shifted and imbricated to create a generous and complex arrangement.

What are the inhabitants of Meier’s villas in the 1980s reading? Marguerite Duras, who won the Prix Goncourt for »The Lover« in 1984; Robert Musil, whose 1930s epic »The Man Without Qualities« was rediscovered by readers in the 1980s; essays by Susan Sontag; Umberto Eco, whose novel »The Name of the Rose« was successfully adapted to the screen in 1986; and, as was to be expected, Milan Kundera and his »Unbearable Lightness of Being«, published in English in 1984, which like no other work of fiction en- capsulates the spirit of the times: a mixture of post-Cold War détente and a sense of unease about the future.

The Style Room would not be complete without the (discreet) presence of a small-scale model of a white Ferrari Testarossa. White like Meier’s architecture, of course, but, more importantly still, white like the Testarossa driven by Sonny Crockett in »Miami Vice« (1984–1990). More than just a pun, it reminds visitors that the tacky TV series marks the rediscovery of Florida’s modernist architectural heritage and its elegant naval references – references which can also be found in the handrails at the Museum Angewandte Kunst. But the Ferrari ultimately symbolises luxury. Because when all is said and done, Meier builds houses for wealthy clients. This makes him the architect of a cultivated elite who enjoy contemporary music, world literature and modern, i.e. timeless, design. A life and taste that we invite you to share here for a moment.

![]()

![]()

Richard Meier, Ein Stilraum

Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt/Main (Germany)

Since April 23, 2015

Curated by Thibaut de Ruyter

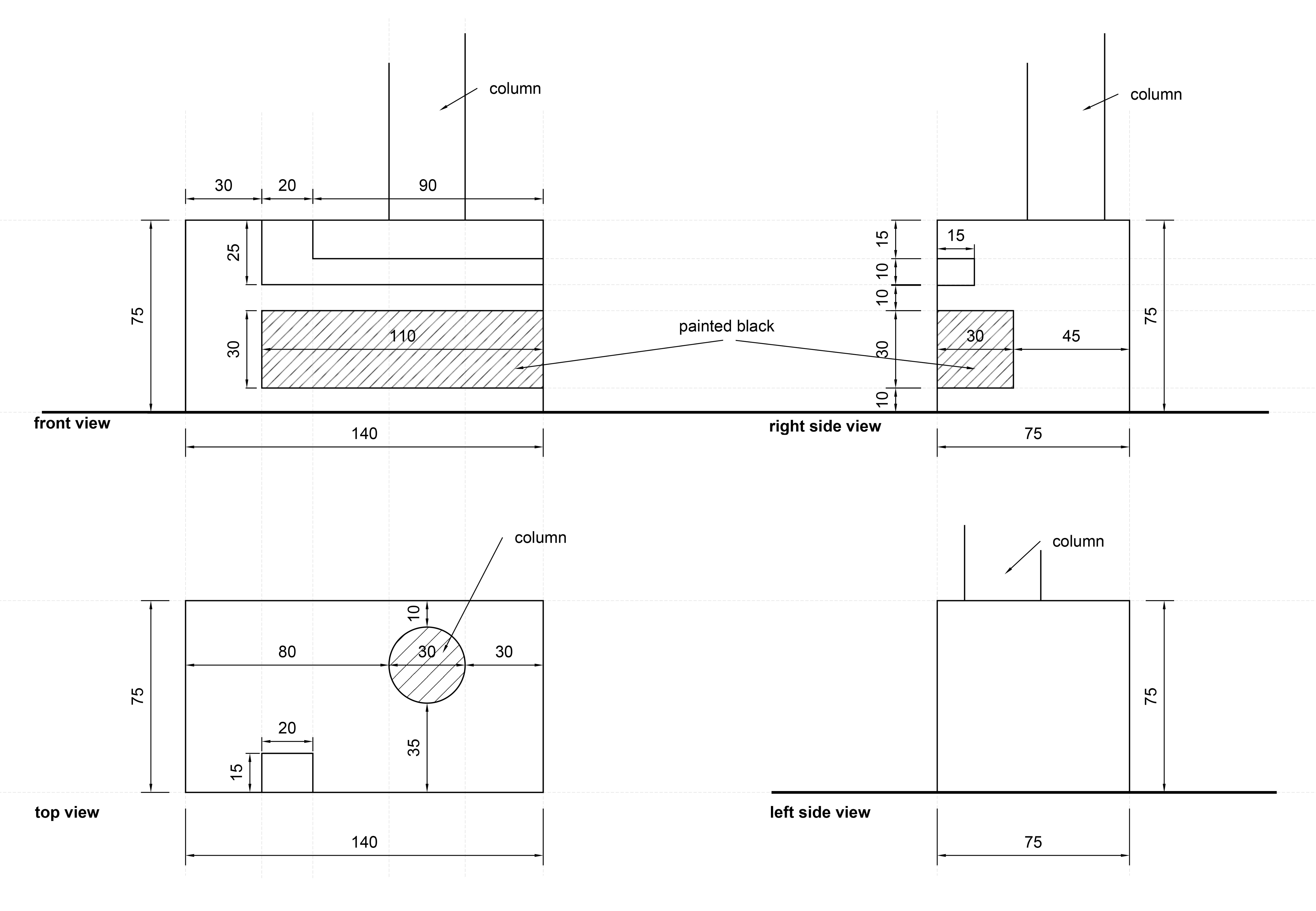

Exhibition architecture: Thibaut de Ruyter (with the assistance of Gaisha Madanova)