INDUSTRIAL (Research)

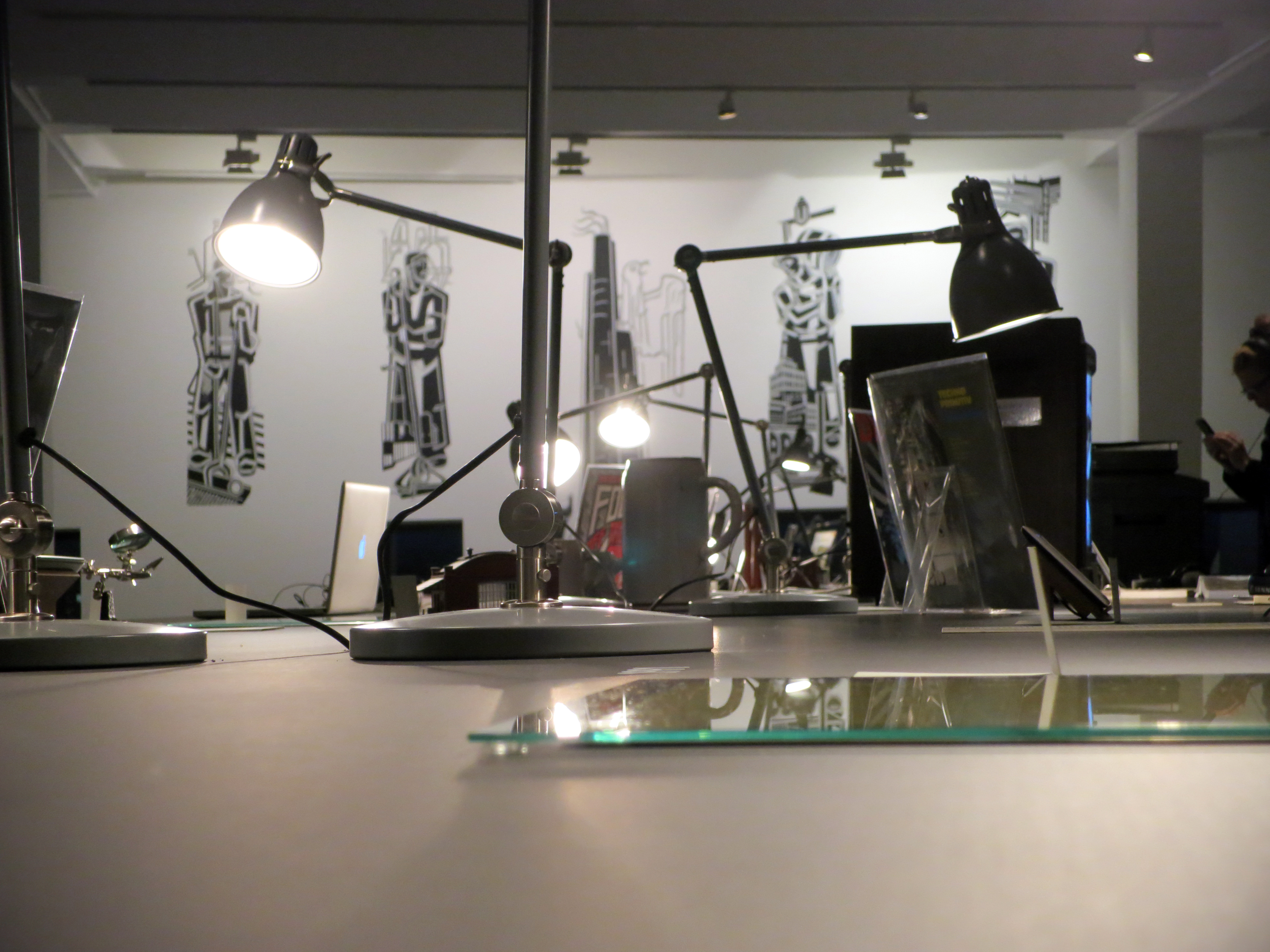

Curated by Inke Arns and Thibaut de Ruyter, INDUSTRIAL (Research) is a 22 meter long reading table displaying books, records, videos and objects related to the european decay and world transformations of industry since the early 1970’s. Visitors are invited to dive in the selection of the curators and to discover the cultural, economical, social, technical or aesthetical impact of industry in our everyday life.

The Impossible Guided Tour

I started writing this text at least three times trying to take readers on a “guided tour” of the exhibition INDUSTRIAL (Research). But each attempt soon left me with the impression of a bad TV show, prompting me to bin the file on my laptop. Writing about the books, films, records and objects on the 22-metre-long custom-built table quickly feels like a presenter’s vain attempt to hold a book into the camera while saying that it is ‘probably the best novel of the year’, ‘an irrefutable source of information’ or a ‘truly and deeply moving testimony’. Basically, it is totally irrelevant.

The real question is: what is the common denominator guiding my decisions when I was asked to choose the documents that would end up on this table? Why this book rather than that, and why this record instead of another? The answer is obvious: the aestheticisation of industry. In other words, the moment when we ceased to look at factories as places of physical and social violence and started to see beauty in them. And how contemporary culture in its wide variety of forms was conducive to this change.

1920

The 1920s, in France as well as in the Soviet Union or Italy, entertained a strange relationship with industry. After the end of the First World War, landscapes, men and minds were scarred, but the poets who witnessed and survived the global conflict were still praising the beauty of machines and the perfume of steel – some ironically, others with an unhealthy fascination. While INDUSTRIAL (Research) focuses mainly the time from the mid-1970s onwards, we felt it was important to provide a prologue and remind visitors that in between the two wars, a handful of creative people saw industry as a means to drive progress and change the world. Whether they were called Dziga Vertov, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Arseny Avraamov, Luigi Russolo or Walter Ruttmann – they all believed in industrial progress. In all honesty, it was a mainly modern ideal (in every sense of the word ‘modern’), a somewhat naive belief in the potential of industry to improve daily life. Only in 1933 did it become clear that industry and its mechanisms of production also made it possible to create one of the most efficient extermination systems in the history of mankind as well as fabricate bombs which, on their own, were able to kill tens of thousands of people in a few seconds while casting an 18-kilometre-high mushroom in the sky.

1973

The year 1973 could well mark the precise point of departure for the history under consideration here. In the 1960s artists who admitted to their interest in industry were few and far between. In 1964 Andy Warhol branded his New York studio as The Factory, and in 1970, with the ecological movement in full swing, a group of electronic musicians from Düsseldorf, in an ironic and smartly provocative twist, called themselves Kraftwerk (power plant). But after the 1973 Oil Crisis it became unquestionably more difficult to poke fun at the condition of industry as plants started closing and unemployment became a fact of life. The ‘Trente Glorieuses’, as the thirty years of post-war economic growth are called in France (regardless of the fact that they never lasted that long), were well and truly over, and the decline of industry created social problems throughout Europe. The artists who at that time began to take an interest addressed these issues frontally, as for instance Bernd and Hilla Becher, who documented and archived the architectural legacy of industry in a manner reminiscent of August Sander. Sometimes, by way of an introduction, we say to visitors that the exhibition celebrates the fortieth anniversary of the Oil Crisis and the endless succession of crises that followed it. No one ever laughs.

1977

Nor did anyone ever really laugh at the provocations of Throbbing Gristle, the band for which the term ‘Industrial Music’ was invented in 1977 (an to which an entire chapter of the exhibition, comprising two records, a video and a book, is dedicated). Whether in their lyrics or their iconography, Throbbing Gristle always approached (and appropriated) politics and sexuality from their extremes. Perversion, radicality, physical violence and black humour were the tools of powerful propaganda (coming from the visual arts scene, they knew that it was not as important to produce as to be the talk of town). Simon Ford’s book Wreckers of Civilisation (1999), which has pride of place on our table, is a wealth of unequalled (and no longer available) information that now costs around one hundred quid. More importantly, it provides implacable proof of a shift from art to music, showing how a bunch of young, cultivated angry people found themselves taking on the production system – not only by creating violent and hitherto unheard experimental music, but by perverting the rules of the musical industry in order to formulate an intelligent and violent critique from within the system.

1977 (redux)

It is highly unlikely that Heiner Müller knew about the artistic and musical experiments of Throbbing Gristle when he was writing Hamlet Machine (1977). And yet, all this took place at the same time, roughly within the space of a few months. The machine that he constructs in this concise and wonderfully poetical text, in a few terse sentences sums up Hamlet’s life, his own, and the political situation in Europe. The “industrial” potential of this machine is miles away from Breton’s and Soupault’s playful lyricism. Why did Müller decide to turn Hamlet’s story into a machine? He writes: ‘I am the typewriter. … I am the data-bank. – I want to be a machine. Arms to grasp legs to walk no pain no thoughts.’ In this text, with its unusual violence as regards both form and content, we find many of the themes that pervaded the 1970s: revolution, left-wing extremism, cross-dressing, sexual liberation, body art, the dissolution of the traditional family cell, the arrival of computers, etc. Yet Müller’s bleak assessment of society is still valid today – which explains why, in 1991, the Berlin band Einstürzende Neubauten quite naturally delivered a radio adaptation of this seminal text, a cornerstone in their discography.

1985

Eroticism, pornography and fetishism. A (shamefully) small section of the table is devoted to Georges Pichard’s erotic classic L’Usine (1979). In this graphic novel, a group of sensuous half-naked women are employed by a bizarre collector to maintain his 238 locomotives. Next to it visitors will find Technø Primitiv (1985), a record by Chris & Cosey, a duo that emerged from Throbbing Gristle and pimped its electronic tunes with a healthy dose of fetishism and sadomasochism (in the lyrics, brimming with references to submission, as well as in the videos and on the album sleeves). The French band Die Form would also have deserved to feature here, had their music not been so bland. The punk movement was born in a shop called SEX run by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren. Merging the worlds of prostitution and fashion, they sold silkscreened T-shirts and fishnet stockings. The Industrial Music scene, pushing the provocation a bit further, looked to extreme forms of sexuality such as fetishism and sadomasochism for inspiration. And when listening to Industrial Music, I often can’t help but think of it as a soundtrack for dangerous rituals. Factory ruins radiate a particular kind of sexual attraction: your car stops alongside the pavement, next to three other cars. You make your way to the fence, looking for the spot where someone using a pair of pliers made a hole big enough for a man to slip through. Wild grass is growing from the cracks between the concrete slabs and slowly reclaiming the site. The windows of the brick factory have been smashed by small pebbles. On one of the walls someone has tagged the words ‘free fuck corner’. As you progress the sound of men breathing heavily draws closer …

1948

The various sections on the table were arranged according to a ‘brutal chronology’ (a principle Müller requested for the edition of his complete works), but visitors are free to start in the middle, go back in time or ignore entire decades. So let us return to 1948, the year when Siegfried Giedion published Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History, an entire chapter of which deals with what the author calls ‘mechanization and death’. In it he talks not about the horrors of concentration camps, but of industrial slaughterhouses – the mechanised production of meat. He describes the continual improvement of slaughtering technologies, the invention of the cold storage room, packing methods (including the asymmetrical design of corned beef cans patented in 1875), artificial insemination, and much more. The illustrations, worthy of a Jules Verne novel, are incredibly violent and cruel, and I doubt that any of this has fundamentally changed in the hundred years that have passed since then. Too often do we forget that industry has taken over all aspects of life – why else would we be referring to the ‘computer industry’, the ‘food-processing industry’ or the ‘porn industry’? Whatever you intend to produce, it must be done according to the rules of animal slaughtering if you want to be competitive. Giedion depicts the nineteenth century, but it would seem that little has changed since then, and his images are literally sickening. I’m sure he would have liked to take a tour in a modern slaughterhouse.

1995

Today another form of pornography is much in demand: ruin porn. When you search Google Image for these two words, you will immediately know what it’s all about (and for once, it’s child-safe): abandoned industrial buildings, walls with peeling paint, collapsing roofs and the occasional bit of office furniture or archives littering the floor. No naked women here, but ruin porn does involve some kind of voyeurism – the feeling of forcing your way into a forbidden place and discovering a forgotten history. We are intrigued by these images in much the same way than the early explorers who discovered Egypt: we see a forgotten world, buildings whose functions we can no longer guess and onto which we project our deepest fears and passions, images of the end of civilisation. And, not least, a possibility to transform them into lofts, the latest fad in real estate.

2012

There are a great many things on this table which, to my mind, are essential: SPK’s fantastic album Zamia Lehmanni: Songs of Byzantine Flowers (1986); the whole collection of books published by the Bechers who since the 1960s have been playing a major role in redefining the way we look at industrial architecture; the 1954 documentary on the Peugeot factories in Sochaux that boasts about the quality of French automobile production; the seminal album Ramrod (1987) by Foetus or, by way of a conclusion, the encounter between Chris & Cosey, the pioneers of Industrial Music, and Nik Void, a member of the young band Factory Floor, on Transverse (2012). I should also mention everything that is missing from the table: the records and stage performances of Club Moral, Tony Garnier’s Cité Industrielle, the history of Japan’s Hashima Island. But choices had to be made, at the expense of gaps or bias (one visitor was aggravated to find a bust of Karl Marx on the table). But at the end of the day, all these exhibits evidence the potential of industry, despite the violence it implies, to be a much richer and more exciting playground than the ruins of Antiquity or the beaches of Portugal – an invitation to play among the rubble.

2013

There is hardly anything industrial (or sexy) anymore about the tower of the Union Brewery in Dortmund. The architect in charge of its renovation made sure to erase the traces of history, the grease stains, the holes in the fence. No one comes here to frolic among the walls or take pictures while thinking of Egypt. At night it is watched over by a young woman with bleached hair and her stately French mastiff, and in some of my dreams the boss’s daughter crosses the courtyard.

Thibaut de Ruyter

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

INDUSTRIAL (Research)

HMKV in Dortmunder U, Dortmund (Germany)

September 14, 2013 — January 26, 2014

Curated by Inke Arns and Thibaut de Ruyter

Architecture by Thibaut de Ruyter